The bittersweet pang of opening a box of finished books

It’s supposed to be an author’s happiest moment. For me, it felt more complicated.

Welcome to Letterhead! If you’re getting this, it’s because you signed up to receive email updates (probably via my website). The literary community on Substack is vibrant and very active, so I’m going to use space instead of my privately-hosted newsletter. I’ll use this space for essays, author interviews, and other book- and writing-related pieces (if you have a book coming and want to talk, please shoot me a note!). I’ll do my best to make this interesting, and I hope you’ll stick around.

Here’s a first essay, about how strange it felt to open my finished copies of The Sky Was Ours, which is out today (order page here). I’ve done some additional writing about the book for other outlets, and pieces are starting to come out elsewhere — links following the essay below.

A few weeks ago, I heard a noise outside the house. It was dark out, my 7-year-old in bed, too late for mail. And yet someone was on the porch. A shuffle of feet. Then, two jarring thuds — once, twice, the sound of something heavy falling.

Rachel and I were in the kitchen, cleaning up after dinner, talking through the next few weeks. My book is out this month, so things are busier than usual — a careful logistical dance of work and appointments, events and travel and childcare. Then: the sudden double-thump. It might have been alarming on a different night. But I knew something Rachel didn’t: Two boxes of books were coming from the publisher. It had to be. What else could have that kind of weight?

“The books,” I said. “I think they’re here.”

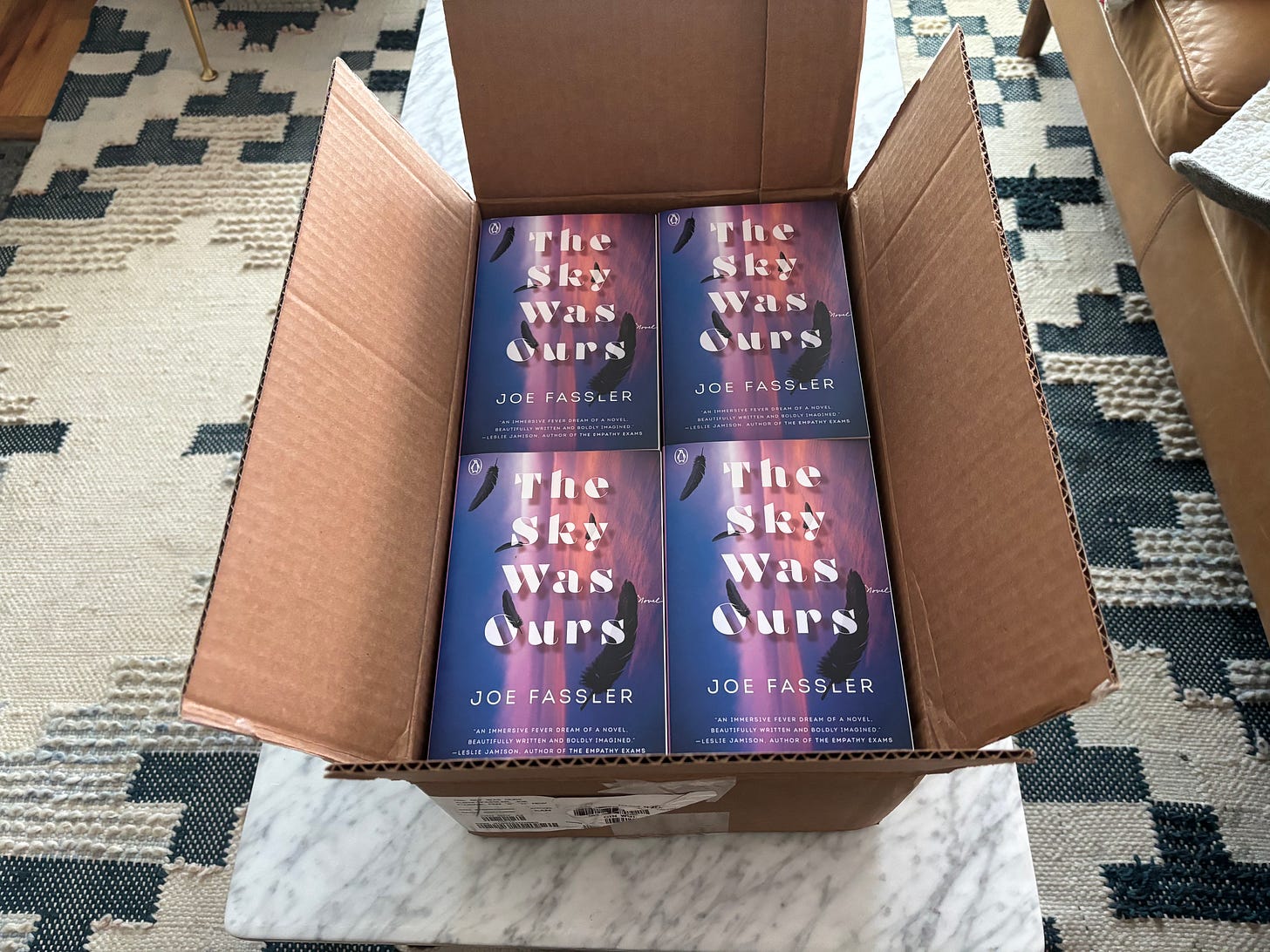

I went out to the porch. And there they were: 40 copies of The Sky Was Ours, the novel it took me more than a decade to write and publish, parceled into two different boxes. The tracking number from the publisher had said Wednesday afternoon, but it was somehow fitting that they came on the wrong day, at an odd hour. Nothing about this process had ever happened the way I’d planned. None of it had ever been on time.

I brought the books into the kitchen, and we opened them. Some part of me knew I should be documenting the moment. The book unboxing video has become a rite of passage, a formula you surely recognize by now: authors tear open the package while on camera, letting viewers glimpse their raw, unfiltered reaction as they confront the end result of years of work. That’s too online for me, but I didn’t even snap a photo. I felt this strange mix of emotions I couldn’t quite parse, a feeling that told me I’d better keep the moment private.

We pulled the tape away, lifted the cardboard flaps. And there they were, my books: beautiful and bright and, most of all, finished. It was supposed to be a joyful moment, and mostly, it was. But what was that other feeling, nagging at me underneath it all? Why did it feel so much like grief?

I started The Sky Was Ours in earnest in the fall of 2012. I’d just gotten my MFA. I’d just gotten married. I was 28, and I had what I thought was a great idea — a novel about flight. The kind of flight I had in mind didn’t involve magic or lucid dreams. My cast of off-beat characters wanted to design a set of wings powerful enough to lift the human body into the air. To build on the work of the Wright Brothers and other early aviators and make a new kind of motion possible — bird-like, unbounded, thrilling. Of course, their idealistic vision would somehow go wrong.

But beyond this basic premise, I had no idea what I was doing. Who were my characters? Why were they obsessed with something so strange? And what was the book about, after all — what larger themes did the visceral, thrilling experience of flying, and falling, really represent? I didn’t know. I didn’t even know how to represent it on the page. What would flight feel like? Even more vexing: how would people outside my little cast of characters react? I tried to imagine how I’d feel, what I’d do, if I stepped outside and saw a person soaring overhead in a pair of bat-shaped wings.

A book is like a gift: once you give it away, it’s not yours anymore.

I wrote in the early mornings, as often as I could. Spending time with my characters and their world — the depressed hinterlands of New York State, a landscape of falling-down houses and failing farms. Minor characters came and went. I wrote scenes and threw them out. My narrator’s backstory shifted, then deepened. I finally finished a draft I could live with in 2015, and then the book went out on submission. It didn’t sell. I licked my wounds for a month or two. Then I kept going.

Something about getting my manuscript rejected changed the writing experience for me. I started to be less attached to the outcome — to publication, to a finished book, to acclaim, to a flesh-and-blood audience, to all the things I thought I wanted. And I started to see my writing as somehow more personal, almost like a religious practice. It was the lens through which I understood the world. I’d get up in the darkness and go the my desk, an antique school desk I’d bought at a Mennonite thrift store in Iowa, with a lift-up chamber and holes where the inkwells had been. And I’d work. I still wanted to sell the book someday; I wanted that very much. But I knew I had to locate a different motivation inside myself, some way to value the hours differently. I forgot about publication, for a while. Or maybe I just despaired that it would ever happen. Whatever it was, I started to see my daily writing as an end unto itself. The writing was the point; there was no other point.

Somehow, that attitude helped me commit to the fictional world I was building more than I ever had before. I spent many more years with my characters: Barry, the brilliant, reclusive inventor and aviation fanatic who against all evidence believes he’s cracked the code to human-powered flight; Ike, his tortured, long-suffering son who yearns for any other life; and Jane, my narrator, the runaway interloper who is caught between them, struggling to weigh her fascination with Barry’s vision against her fears about who he might really be. Over time, they became almost real to me — their histories, their failings, the way they spoke. There were weeks I spent more time with them than any person living.

There were also times I lost track of the book. When my son was born. In the first months of the pandemic. But for years, it was there for me — a place I could literally go, too. It wasn’t real, of course I knew that. I was making it up. But it did often feel like coming home again, the moment I shut my office door.

Where is that world now? In a literal sense, it still exists: You can find it in between the covers of The Sky Was Ours. (Or, at least you will be able to, when the book comes out next week.) But for me, personally, a portal has closed forever. The book is finished. I will never write about those characters and their corner of the universe again.

That’s what I couldn’t help thinking, as I touched the finished copies with my hands. I was happy. Of course I was. But that gladness was intertwined with a surprising sense of loss. I flipped through the pages, the words fixed there in black and white, as if written by someone else. I felt how much a book is like a gift: Once you give it away, it’s not yours anymore.

There’s a famous children’s book about a wardrobe with a wormhole in the back. I understand that experience, what it’s a metaphor for — because writing can be like that, a way to escape out the back of reality into something new. The finished copies meant that experience was over. I could try enter that particular wardrobe again, brush aside the coats, but I know the trick will have lost its magic. There will only be the smell of mothballs, and an unforgiving wall, where once I’d found a secret gateway to another world.

Do we have a word for that? For the writer’s loss of what had never been there to begin with? Whatever it is, I feel it acutely now. I feel it as I try to start another book, the characters and themes still faltering and new. Who are these people? They’re strangers to me still. But I try to remind myself that the old characters were also hard-won. Maybe that’s what writing is: an act of faith that, someday, the words will come alive again, no matter how flat and lifeless they seem now.

I finally took pictures of my box of books today, a week days later. Something to put on Instagram, the featured image for this post. The book is here, I’ll say. It’s real now. It exists. And then the part I won’t say, except right here: This beginning is also an ending.

As books gain a public life, they lose something too — becoming finite and forever past-tense, the way we do in death. It’s all right, I accept it. The Sky Was Ours was mine, and now it’s yours.

Elsewhere: Lit Hub has called The Sky Was Ours a “darkly atmospheric” debut in its roundup of new books out today (Amy Tan! Jane Smiley!). I’ve recommended 7 other novels that feature fictional inventions in Electric Literature, which has also run an excerpt from the novel with a gorgeous introduction by Kyle McCarthy. And I’m doing some events in Denver and New York, with other dates to come.

Congratulations. This was really interesting to read. Wow I try to finish a rewrite and preparation for some agent meetings in June. Welcome to Substack!